The word “lobotomy” tends to conjure images of terrifying brain surgery and people stripped of their personality. In reality, lobotomy was once considered cutting-edge medicine. In this guide, we unpack what lobotomies actually were, why they were used, how much harm they caused—and how modern trauma-informed, ethical mental health care is completely different.

This article is for education only and does not replace medical or psychiatric care. If you are in crisis or worried about your safety, please contact local emergency services or a crisis hotline immediately.

- Then: Irreversible brain surgery, often without consent.

- Now: Evidence-based talk therapy, medication, and collaboration.

- Goal today: Reduce symptoms while protecting who you are.

A lobotomy was a brain surgery intended to treat severe mental illness by cutting or destroying connections in the frontal lobes—especially the prefrontal cortex. Doctors hoped this would calm agitation, psychosis, or intense emotional distress. In practice, lobotomies often caused permanent changes in personality, thinking, and independence. Today, lobotomy is considered a discredited and unethical treatment.

Early psychiatrists believed that mental illness stemmed from “stuck” or “overactive” brain circuits. They thought disrupting those circuits could relieve suffering. At the time, there were no antipsychotic medications, limited understanding of trauma, and very few effective treatments. Many people with psychosis or extreme mood symptoms spent years in overcrowded institutions with little hope of improvement.

Quick facts about lobotomy

- First procedures appeared in the mid-1930s; peak use was the 1940s and early 1950s.

- Used for severe psychiatric diagnoses—especially schizophrenia, major depression, and bipolar disorder.

- Many patients were institutionalized and had little power to refuse treatment.

- Common outcomes included emotional flattening, cognitive impairment, and loss of independence.

- Lobotomy is no longer used in standard psychiatric care and is widely regarded as a historical example of harm.

If you or a loved one has a diagnosis like schizophrenia and this history feels unsettling, you are not alone. Modern care for psychosis looks very different. For a grounded overview of what treatment looks like today, you can read: All About Schizophrenia: Symptoms, Causes, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Everyday Management .

Why did doctors turn to lobotomies at all?

It can be hard to imagine today, but when lobotomy was introduced, psychiatry had very few tools. Many people with severe psychosis, chronic mania, or deep depression were hospitalized for years. Facilities were overcrowded, under-resourced, and often unsafe. Families and clinicians were desperate for anything that might help.

In 1935, Portuguese neurologist António Egas Moniz introduced “prefrontal leucotomy,” cutting white-matter tracts in the prefrontal cortex. He claimed that some patients calmed down and became easier to manage, which led to global interest. Moniz later received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for this work—an award that remains controversial because of the long-term harm lobotomy caused.

In the U.S., neurologist Walter Freeman and neurosurgeon James Watts adopted and popularized lobotomy. Freeman later developed the transorbital “ice-pick” lobotomy, which could be done quickly, with fewer surgical resources. This speed led to wider use—but also meant more people were operated on without thorough assessment or follow-up.

When you compare that era with current trauma-informed approaches, the contrast is huge. Today, care is grounded in collaboration, research, and respect for autonomy. For example, if you’re trying to understand how emotional pain can be treated without drastic measures, you might explore: Repressed Emotions: How to Recognize, Process, and Heal or Alexithymia Treatments: Unlock Emotions with Proven Therapies, Mindfulness, and Practical Skills .

How was a lobotomy performed? (Non-graphic overview)

Lobotomies were carried out in several ways, but all aimed to disrupt connections in the frontal lobes. Two main approaches emerged: the standard prefrontal lobotomy and the transorbital “ice-pick” lobotomy.

1. Prefrontal lobotomy

In a typical prefrontal lobotomy, a neurosurgeon drilled small burr holes in the skull—usually above the eyes or on the side of the head. They inserted a surgical instrument through the holes and swept it through the white-matter tracts, severing pathways between the prefrontal cortex and deeper brain regions involved in emotion, motivation, and cognition. The goal was to disrupt “faulty” circuits causing symptoms.

2. Transorbital “ice-pick” lobotomy

Walter Freeman later developed the transorbital technique, which involved inserting a thin, ice-pick-like instrument through the upper eye socket, just above the eyeball. The instrument was tapped through the thin bone at the top of the orbit, then moved side to side to cut frontal lobe connections. This could be done quickly, sometimes without an operating room, making it popular in institutional settings—despite serious risks.

Conditions lobotomy targeted

- Schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders

- Severe, recurrent depression

- Bipolar disorder and manic states

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

- Extreme agitation or aggression in hospitals

What doctors hoped to see

- Less agitation and aggression

- Reduced hallucinations or delusions

- Quieter, more “manageable” patients

- Fewer self-harm attempts

From a modern perspective, we recognize that “calmer” is not the same as “better.” Emotional numbing, cognitive impairment, and dependency are not healing. Today, when people struggle with intrusive memories or overwhelming emotion, trauma-informed therapies such as EMDR focus on processing—not erasing—experience. You can learn more about this in: EMDR for Childhood Trauma: Does It Work? NYC Therapists Explain .

Who received lobotomies—and what happened afterward?

Historical records suggest that tens of thousands of lobotomies were performed worldwide, with particularly high numbers in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Scandinavia. Women were lobotomized more often than men, and in some cases, children or adolescents underwent the procedure.

Common long-term effects

- Profound personality changes

- Emotional blunting or “flatness”

- Difficulty planning, focusing, or making decisions

- Incontinence, seizures, or other neurological problems

- Loss of independence in work, relationships, and daily tasks

- In some cases, death from the operation or its complications

Experiences like emotional numbness, dissociation, or fragmented identity are now understood in the context of trauma, personality, and dissociative disorders—and treated with careful, attuned psychotherapy. If you’ve ever wondered whether past trauma could explain emotional shifts, you might find resonance in: Dissociative Identity Disorder: Understanding the Complex Reality of Multiple Personalities .

Many people also struggle with complex mood and personality patterns that historically would have been misunderstood or misdiagnosed. Today, conditions like depression, narcissistic personality disorder, ADHD, and OCD are approached with nuance instead of blunt tools. For example: Therapist for Narcissistic Personality Disorder , Adult ADHD Symptoms: Recognizing the Signs and Finding Relief , and ICD-10 Codes for OCD: What You Need to Know .

Why did lobotomies fall out of favor?

By the 1950s and 1960s, lobotomy’s risks became impossible to ignore. Several key shifts helped bring the practice to an end:

- Medication breakthroughs: The introduction of antipsychotic medications like chlorpromazine allowed many people with psychosis to experience relief without brain surgery. Antidepressants and mood stabilizers soon followed.

- Ethical evolution: The rise of bioethics, disability rights, and patient advocacy brought questions of consent, coercion, and human rights to the forefront. Irreversible surgery on vulnerable people became harder to justify.

- Long-term outcomes: Follow-up data showed that many lobotomy patients remained disabled or dependent, even if they were less disruptive in hospital settings.

- Policy and law: Over time, regulations around psychosurgery tightened, and in many places, lobotomy was banned or restricted to extremely narrow indications.

At the same time, psychotherapy became more sophisticated, moving away from purely institutional care toward outpatient and community-based models. Today, people with depression, bipolar disorder, and PTSD have access to a wide range of non-surgical options—from cognitive behavioral therapy to EMDR to trauma-informed approaches. To see how depression is approached now from a diagnostic perspective, you can explore: What Are the Depression ICD-10 Codes? .

Are lobotomies still used today?

Classic lobotomy is no longer used as a standard treatment for mental illness. In many countries, the procedure is explicitly banned or so tightly controlled that it effectively does not occur. When people speak about lobotomy today, it’s almost always as a cautionary tale about how far psychiatry has come—and what happens when power and fear go unchecked.

Modern brain-based treatments (rare and highly regulated)

In very rare, treatment-resistant cases, carefully targeted neurosurgical procedures may be considered—such as deep brain stimulation (DBS) or tiny, precisely placed lesions for severe OCD or chronic pain. These interventions:

- Are not the same as historical lobotomy.

- Are used only when multiple therapies and medications have failed.

- Require extensive evaluation and ethical review.

- Are far more precise, with the goal of minimizing harm.

For the vast majority of people, mental health treatment today involves psychotherapy, lifestyle support, and, when appropriate, medication. For example, someone with bipolar disorder might work with a therapist on mood tracking, sleep routines, and coping tools while also collaborating with a psychiatrist. To see what this can look like in everyday life, you can read: Bipolar Disorder in NYC: Mood Tracking, Sleep & Local Care .

Teen depression, which might once have been misunderstood or ignored altogether, is now recognized and treated with early intervention. If you’re a parent or caregiver, you may find it helpful to review: Teen Depression: 5 Hidden Signs Every NYC Parent Should Know .

From lobotomy to collaborative, trauma-informed mental health care

The story of lobotomy is not just about a single procedure—it’s about how we think of people who are suffering. In the past, treatment often prioritized quieting symptoms and making institutions easier to run. Modern mental health care aims to reduce suffering while preserving—and even strengthening—your sense of self, relationships, and quality of life.

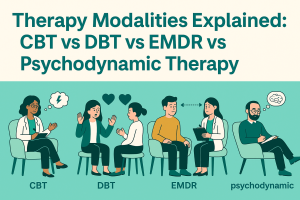

How modern therapy is different from lobotomy-era psychiatry

- Informed consent and shared decision-making: You have the right to understand your diagnosis, ask questions, decline treatments, and get second opinions.

- Evidence-based methods: Approaches like CBT, DBT, EMDR, and psychodynamic therapy are chosen based on research, not guesswork. You can see an overview of these in: Therapy Modalities Explained: CBT vs DBT vs EMDR vs Psychodynamic Therapy .

- Reversibility and flexibility: Medications can be adjusted, therapy goals can be revisited, and treatment plans can change as your life changes. There’s no irreversible “on/off switch” like lobotomy.

- Whole-person focus: Care addresses physical health, relationships, work, and meaning—not just symptom scores.

- Trauma-informed lens: Many modern therapists understand how trauma shapes survival strategies, flashbacks, dissociation, and emotional numbness. Instead of trying to remove your reactions, they help you understand and reshape them.

For example, trauma-informed work with veterans recognizes how triggers and flashbacks are rooted in real experiences. Rather than reaching for drastic interventions, therapists support grounding, processing, and rebuilding a sense of safety. You can see what this looks like in practice here: Veteran PTSD Triggers: How to Manage Flashbacks (NYC Resources) and PTSD Nightmares: 5 Grounding Techniques to Wake Up Calm .

Need support now? You deserve care that honors your story.

If you live with depression, trauma, bipolar disorder, psychosis, or emotional numbness, it is normal to feel wary of mental health systems—especially after learning about lobotomy. At TherapyDial, our therapists use evidence-based, collaborative approaches rooted in respect and consent, never coercive procedures.

Request a confidential consultationFrequently asked questions about lobotomies

Did lobotomy ever actually help anyone?

A small number of patients were reported to show reductions in agitation or psychosis after lobotomy, which helped fuel its early popularity. But these apparent gains often came alongside major losses in cognitive function, emotional expression, and independence. When we consider the full picture, lobotomy is now viewed as an unacceptable trade-off.

Are lobotomies still performed anywhere?

Classic lobotomies are no longer part of standard psychiatric care and are prohibited or heavily restricted in most countries. Modern neurosurgical interventions for mental health are rare, highly regulated, and much more precise.

What replaced lobotomy in mental health treatment?

Lobotomy was replaced by a combination of psychotropic medications (such as antipsychotics and antidepressants), evidence-based psychotherapy, community supports, and a rights-based approach to care. For example, still-stigma-laden conditions like depression are now understood through careful diagnosis and coding, as described in What Are the Depression ICD-10 Codes? .

How do I know if my treatment is safe and ethical?

Some good signs: your provider explains options in plain language, invites questions, discusses risks and benefits, respects your right to say no, and encourages second opinions if needed. If you ever feel pressured or shamed, that’s a signal to seek a provider whose practice aligns with modern ethical standards.

What if I feel emotionally numb, but I’m afraid of being “changed” by treatment?

Emotional numbness is common in depression, trauma, alexithymia, and burnout. Modern therapy doesn’t aim to turn you into a different person—it focuses on helping you feel safer, more present, and more connected to yourself and others. If you identify with emotional disconnection, you may resonate with Quiet Depression in Partners: How to Help Without Words .